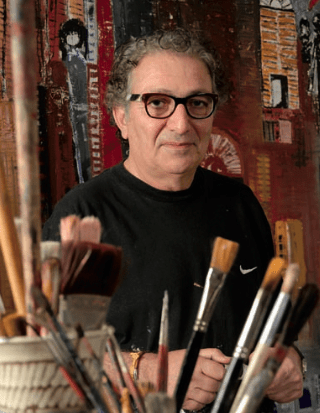

Nahla Ink is happy to share this deep meditative essay on Ahmed Farid’s artwork by Diego Faa.

Ahmed Farid’s artwork is featured on Nahla Ink Online Journal throughout the month of April 2020.

Guest Post: Diego Faa

From his very first formulations of pictorial research, the art of Ahmed Farid has staged a closely-confined and relentless conflict between the attempt at complete elimination of the figurative and the symbolically fierce resistance of his own cultural roots of expressionist stamp. Nevertheless, this structural feature of much of his production should not be read as an unresolved issue within Farid’s universe: on the contrary it is the essence of the same, the generative thrust behind every single one of his artistic creations.

What we have then is not two different paths, but a differently parallel itinerary which can consistently open up towards multiple stylistic and technical possibilities. Moreover, being born in Egypt, growing up with American cultural mythology, travelling through the world and being penetrated by the explosion of avant-garde art history movements can plausibly lead to such a

confrontation-clash with one’s own nature.

Indeed, both as a man and as an artist, Ahmed Farid is influenced by this formative and chronologically dissociated melting-pot which manages to combine figurative echoes drawn from the experience of Gazebia Sirry with compositional reminiscences that look to Nicholas de Staël and explosions of gestural colour influenced by the work of de Kooning filtered through the itineraries of Adel el Siwi.

What Farid implements before the white canvas is a continual balancing of portions of cultural awareness. This is a staging of his entire experience – the life path first and art afterwards – that transcends technique to achieve a full and total personalisation of making art.

Within this dialectic the elimination of the figurative stroke is hence not experienced by Farid as a conquest connected with the indissoluble twentieth-century dichotomy between mimesis and reality, but as the assertion of a pictorial autonomy capable of projecting only itself, devoid of all belonging. This path, cleared of dogmatic obstacles, restores a strong sense of freedom to his art.

The absence of an immediate and univocal responsibility transforms reality into visual experience, into poetry balanced between the spiritual and material physicality. The dreamlike and sometimes disturbing quality of some of his works celebrates an excited creative debate within the artist. This may be resolved in an explosion of colour – or in the absence of it – which starts from a fixed point and is propagated, expanding to fill the entire canvas. In a chromatic courtship, the shades come close and reciprocally balance each other without ever overlapping.

The subject of the works is never a fixed image but a gestural automatism, an evolving flow that merely hints at reality. From this perspective, the sign becomes rational transcription in a succession of stains, clots of matter and emotional writing. Order makes way for an apparent disorder, pursuing a logic that is defined, within the compositional tangibility, in a stylistic deformation conceived to reflect a mood of absence and of the persistent meshing of distance from the figurative and its evocation in abstract terms.

The shapes, that are no more than sketched or even whispered, appear unstable as if awaiting a different dimension, an interior space devoid of narrative. The apparent anxieties make way for feverish explosions of inner peace in a physical world that is scarcely able to contain the imaginative enormity of Ahmed Farid’s work.

The large-scale works in particular impress on the observer a sense of sublime contemplation, an invitation to venture into the disturbing meanders of one’s own unconscious. Using grounds of variably even colour, the artist concentrates on a labour of fragmentary brushstrokes and material residues that emerge as symbolic hostages in the precarious tangle of the magmatic colourings.

This sort of stylistic metaphor yields canvases loaded with thick, at times almost creamy paint, where the crowding of signs, shapes and colours tends to entrap figures and portions of humanity with an archaic flavour. These figures appear to be crushed and sorely tried: distraught and disintegrated souls in search of their space. It is, therefore, a strongly human situation, capable of evoking a primeval history of symbolic significance.

The identifying image is concealed and then proposed to the gaze, evading winking impositions to knit up a sort of metaphysical intimacy with what surrounds it and with the observer.

The slender non-figure figures, which appear to emerge from the depths of the canvas, the strong tonal nuances and a natural inclination towards the creation of layers of matter give rise to a transfigured consistency and a lacerated polyphony. The result is a type of expressivity which becomes possible only by arriving at a mediation between tangible perceived reality and a timeless space.

This geography – in which delicate figures hug masses of compact colour – is what makes up Farid’s art. Such a deeply consistent and solid equilibrium in chromatic terms is achieved through the juxtaposition of admirably balanced sections of colour and constant comparison with the intensity of the light which appears to orient the tesserae of shifting gradations.

In the process of creating the work the artist checks that every element tends to and generates unity, suspending all possibility of temporary solution. Even a faint brushstroke, a light touch, or the adjustment of a balancing of percentages of light can upset the overall vision.

The violence of the pictorial gesture, of expressionist stamp, appears to be guided by just a few decisive, confident gestures devoid of second thoughts; in actual fact, the final result of the work is the fruit of a very lengthy creative process. The artist indeed addresses the canvas again and again, correcting and retouching tiny parts of colour, adding or removing small units of matter, such as gold or silver leaf, and overlaying techniques and materials.

Watching Ahmed Farid at work, we have the chance to perceive the secular sacredness with which he approaches his concept of making art: the three steps backwards which he frequently takes to get a larger view of the work encapsulate the entire cosmos of imagination and instinctive creation that characterises his production. It is only by achieving this short distance that we – using his key – can see the asymmetrical totems in movement, continents adrift and figures in search of an impossible definition.

Diego Faa is a Professor of Art History, Management of the Art System and Communication for Cultural Promotion based in Florence, Italy. Faa is also an arts curator and organiser of temporary exhibitions in galleries and public spaces as well as being a reference point for some artists’ archives.