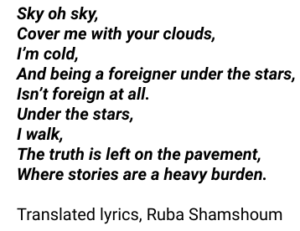

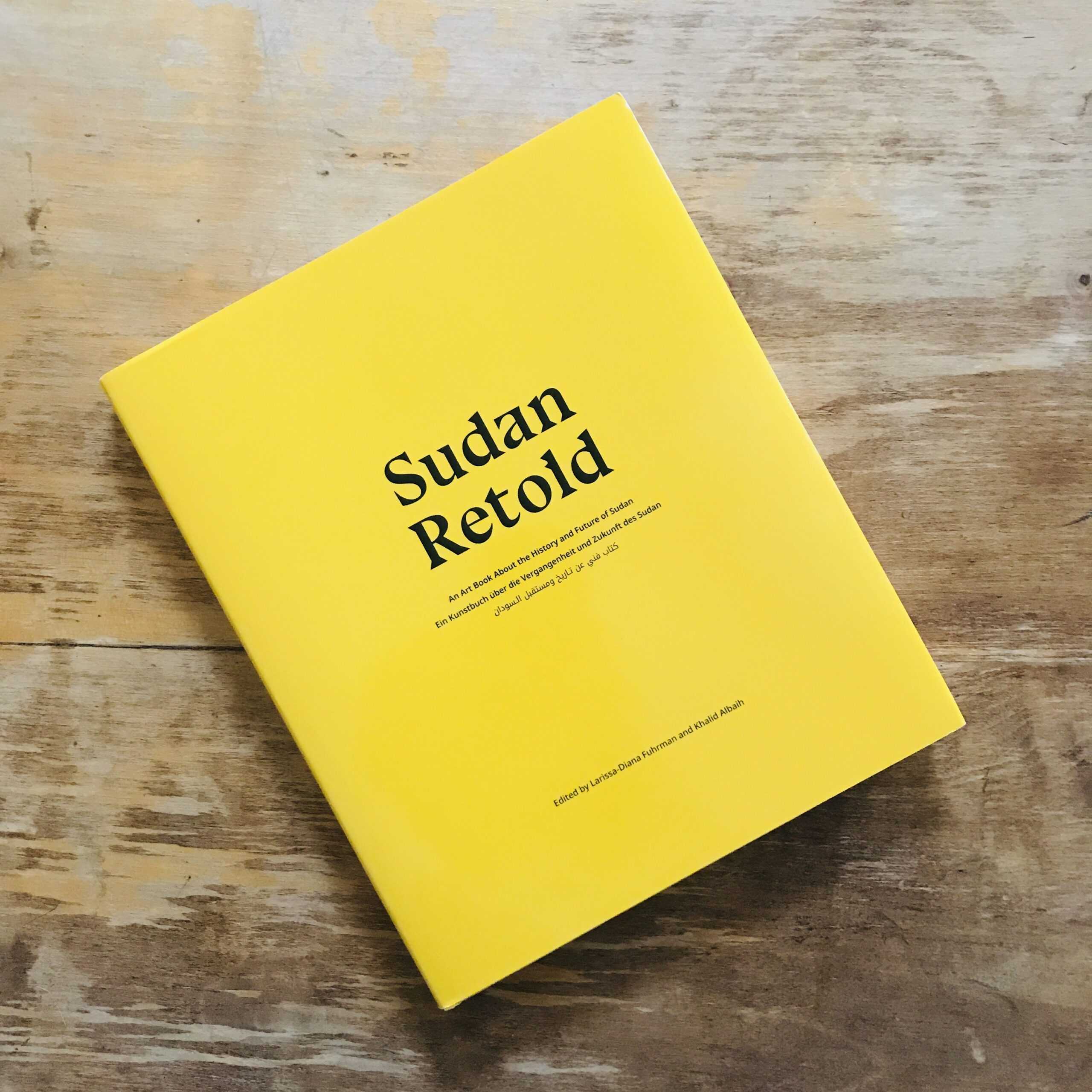

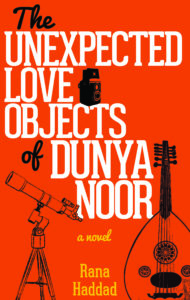

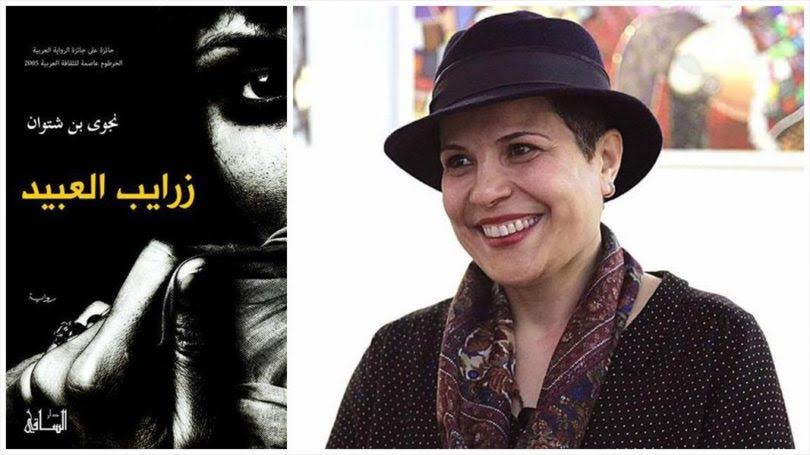

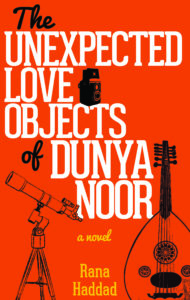

At the highly anticipated book launch held at the Holland Park Daunt bookshop, author Rana Haddad read out a few paragraphs from her debut novel ‘The Unexpected Objects of Dunya Noor’. The humorous passages got the informal gathering in fits of laughter; and, soon after, we were treated to the beautiful voice of Lina Shahen, whose Arabic songs transported us to an enchanting world of music originating from the Levant and a tune about people being neighbours with the moon.

With that Fairuz song in mind and Haddad’s fun, light-hearted and playful spirit in storytelling, I relished the book in no time. In it we follow the tale of Dunya Noor, a young half-Syrian half-English heroine, with green eyes and unruly curly hair, whose wild nature takes on the status quo of the culture she is born into circa the 1980s. She is a young lady who is no way minded or afraid by rules, be they set by parents, school, religion, neighbours or even if dictated down by a cruel military regime.

Growing up in the Mediterranean port city of Latakia with her mother Patricia and successful heart-surgeon father Dr Joseph Noor, she first confuses them at the age of eight when she acquires an old Kodak camera that becomes her most prized treasure and constant companion. Then they are worried when she is seen walking hand in hand with the ‘wrong’ sort of boy in her naïve quest to find out what true love is and understand its nuances. Real trouble however occurs when she refuses to attend a political demonstration with school and indicates to her teacher that she is against the Baath Party.

Quickly to protect her from punishment and public humiliation, she is exiled and sent to her maternal grandparents in England, where she completes her education and also fatefully meets Hilal Shihab. The son of Muslim tailors from Aleppo, he is himself obsessed- not with a camera but with a telescope, notebooks and fountain pens – and eager to explore the mysteries of the moon, the stars and all that lies beyond in the universe. They fall for each other and are blissfully happy in London, until a letter arrives that leads to both of them returning to Syria circa 1994.

It is truly at this point of the novel that the plot thickens and is kick-started by the mysterious disappearance of Hilal and Dunya’s brave determination to find him. Her search in Aleppo leads to many unusual twists, turns and surprises, as we meet newer characters who transform the tale into something much more multi-layered, complex and dramatic. The author succeeds in creating suspense that lasts right up until the end, where although most of the issues are resolved, a key one is left open to our imagination.

Haddad does an incredible job of putting forward deep dimensional personalities who are neither perfect nor complete, but who are human, subject to fault and error as well as redemption. This book is also a meditation on the nature of true love, on the varying degrees and shades of freedom available to us, on the power of creative expression; and, on how poetry, music and song can enrich lives.

Just like a serenade tenderly composed, the novel honours Syria’s beautiful cities and its diverse inhabitants, as we are led to visit its hidden gems and discover its cultural landscape and social fabric during a particular period in the country’s evolving history. I highly recommend it but just with a warning to prepare for the highly unexpected!

The Interview

Nahla Ink: The book is full of references to astronomical phenomenon. Are you a keen astronomer? Do you believe there is a connection between what is in the skies and what happens on the Earth and impacting on people’s lives?

Haddad: “I’m not into astronomy in a technical or scientific sense but I find it imaginatively beautiful. As a child I had a plan to become an astronomer, or an astronaut, but I quickly gave that idea up when I realised it would require me to study physics when I was more interested in the Arts.

“We do live on a planet that travels through space and it is easy for us to forget how small we are because of our ego-centric and self important ways, so I think we should always be aware of the stars and the vastness of the universe to help us put things in perspective.

“Also, I think that there are patterns in the universe, which we don’t understand and which we have always sought to understand and looking at the movement of the stars is one way humans have to do that. I have no idea whether stars have an impact on us directly but I think they mirror the way we are with one another. We orbit each other, we influence each other, we mirror each other and we can have enlightening or destructive effects on each other, we circle each other, we lose each other, etc.

Nahla Ink: There are references to fortune telling and astrology that become relevant to the plot. Is there any reason why you utilised this to carry the story forward?

Haddad: “The fortune telling is just a kind of metaphor for fear and how fear can lead people to losing trust in their own gut instincts and hearts, and how when this happens we can become victims of manipulative or random external forces, including distorted and manipulative versions of religion, politics and social norms which are based more on control rather than love, fear rather than freedom.

“But Suad and Said, characters in the novel, were vulnerable to such fear because they had in turn been ostracised by their communities for choosing their love for each other over obedience to irrational rules and norms. Another way of putting it, is that I think people can lose their souls when they follow the advice and instructions of others, rather than following their own desires and intuitions. This is why totalitarian government and fundamentalist religions and even the media and advertising can have such destructive effects.”

Nahla Ink: Dunya’s camera is not just her best fried but an obsessive comfort blanket that she takes with her everywhere. Is there a reason why she can’t filter reality unless she views it through the lens?

Haddad: “I see her camera as just a way of describing her consciousness, her need and insistence and willingness to look at the world squarely in the eyes, and properly, and to understand it on her terms – as much as possible, like a scientist who doesn’t take things at face value, but needs to find proof. So she is not one easy to brainwash and that is why she is a thorn in the side of her parents and society, but also a gift to them, if only they would listen and learn.

“I kind of want Dunya to be about how elders should also sometimes listen to their children, not only the other way around. And how children and young people can have a purer untainted way of seeing the world, which adults must re-member and restore in themselves, rather than trying their hardest to de-form the children’s souls and break them and force them to toe the line. I know I am being idealistic like Dunya when I say this, but I believe it strongly. Also, I think it’s the only way for societies to develop and evolve.”

Nahla Ink: Dunya’s character is feisty, stubborn and she doesn’t yield to the societal norms of the Assad dictatorship and the patriarchal system surrounding her. Do you think someone like Dunya would have got away with the public disobedience she committed in real life?

Haddad: “I think she would’ve if she was from the right sort of family and also if she was publicly punished and apologised and never repeated the offense again. This incident in the book is based on something I have witnessed, so I know that something like this can happen without the child being disappeared, though she was certainly lucky.”

Nahla Ink: Another key female character in the book is just as feisty and stubborn and even more daring than Dunya. Can you tell me more about what inspired Suha?

Haddad: “It is strange because Suha literally came out of nowhere, but after I wrote her, I realised she is many many Arab women and maybe a part of me is also like her. She is feminine power in its essential form – she is art, music, sensuality and love. Maybe she is a kind of Aphrodite. A force that was once very strong and very elemental in our part of the world, as well as Greece and Rome, and without which the world would be very dull and boring and without glamour or beauty or even meaning.

“So she must never be obscured or hidden, and she must always be visible and never bought or sold. She must be celebrated and accepted and loved and integrated. That is the symbolic aspect of Suha. But Suha the character is the same, if she is rejected and denied, everyone in the book related to her, will be lacking something essential in themselves and in their lives.”

Nahla Ink: Can you expand on the nature of the love that the characters are all trying to figure out? Is it foolish? Is it real? Is it ephemeral? Is it tragic?

Haddad: “I don’t think it is a foolish love, but this sort of love is complex and leads to self-knowledge. It’s not a love that can fit neatly into society or helps tribes cement themselves and procreate. It is love for the sake of love, and I think it is very important.”

Nahla Ink: Dunya’s father seems pro-Assad and represents the corrupt elite yet he somehow redeems himself. How would you describe Dr Joseph Noor?

Haddad: “The father is simply someone who wants to be socially successful and in a country like Syria, one has to co-operate with the established order, like in any other country, let’s face it. If and when the Assads are gone, there will be another established order and people like him will have to find a way to be on the right side of it. This is the way of the world whether we like it or not.

“Perhaps one can call Joseph ‘a conformist,’ whereas his daughter is a ‘non-conformist’. A conformist always wants to win the carrot offered by Power, whereas the non-conformist does not worry about the stick, as long as they can have their inner freedom. They are risk-takers and more exploratory characters. They like the new, not the old, they like to create rather than to put all their energies into conserving things as they are ‘conservatives’ or hark back to a bygone age and trying to mimic it.”

Nahla Ink: The book has many of the elements usually found in Shakespearian comedy: the struggle of young lovers to overcome problems as a result of the interference of their elders; an element of separation and reunification; mistaken identities involving disguise; family tensions usually resolved in the end; complex, interwoven plot-lines; and, finally, the frequent use of puns and other styles of comedy. Would you agree?

Haddad: “I have been told about the Shakespearean elements and none of them were conscious or intended. But I loved Shakespearean comedy as a student and perhaps it has seeped in. But, also, I have a theory that Syria is very Shakespearean. Joseph Noor would even argue that Shakespeare is an Arab and that his real name was Sheikh Isber!”

Nahla Ink: How was the process in writing the book and how long did it take you to put idea to final published novel?

Haddad: “It took me many years and I had long breaks due to health problems and also working in Media. So I had to take time off and go into a different frame of mind. The world of this book is the world I feel more comfortable in, rather than working in Media, so it became harder and harder to want to do the latter especially as the war in Syria wore on, and the media narrative became more distorted, dangerous and riddled with misinformation.”

Nahla Ink: Lastly, what influences your style of writing and what kind of literature do you particularly enjoy reading? Has the latter impacted on the former?

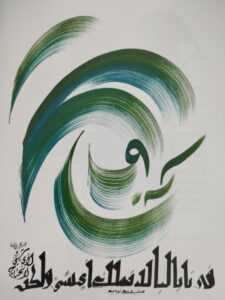

Haddad: “I love poetry and fiction that is both fun but deep, I’m more interested in the music of words and their meaning rather than in plot for the sake of plot. So, for example, I would never be able to read a thriller, but I could read a verse of poetry over and over again for days.

“I did also write poetry in my early twenties and much of it was published but I didn’t pursue publication too much as I knew I wanted to write novels, but I was too airy-fairy when young to be able to write a novel, so it took me a while to grow up and be able to write over a longer canvass than a poem.

“Some of the first novels in English I read were by Virginia Woolf and also Salman Rushdie, I loved Coleridge, Khalil Gibran, Nizar Kabbani, Iris Murdoch, Milan Kundera, Antoine Saint Exubry, Roal Dahl, and, of course, Sheikh Isber!”

Biographical Note: Rana Haddadis half Dutch-Armenian (mother) and half-Syrian (father). She grew up in Latakia in Syria, moved to the UK as a teenager, and read English Literature at Cambridge University. She has since worked as a journalist for the BBC, Channel 4, and other broadcasters, and has also published poetry. ‘The Unexpected Love Objects of Dunya Noor’ is her first novel, published by Hoopoefiction, an imprint of AUC Press.

Note: This article was first published circa June 2018