In sunny Jeddah, Saudi Arabia a young Arab woman is usually tucked away in a top-floor studio at her parents’ house in a peaceful residential area. Spending over twelve hours a day with a sharp 9am start to midnight, she is focused on creating an interpretation of Islamic art that of its nature carries a heavenly dimension and astral references. In this super tidy space, she must centre herself for the precision and skill required to make her divine paintings, drawings, woodwork and ceramics.

Dana Awartani is the 27-year-old Saudi-Palestinian artist who has already attracted international recognition for her artwork, exhibited in several group shows and is represented by the prestigious Athr Gallery in Jeddah; where she is currently taking part in the ‘Language of Human Consciousness: Arts Inspired by Geometry’ exhibition and where she will also have her first solo during Ramadan 1436 AH. Aside from her immersion in this spiritual discipline, she is a modern girl in every way, with an Instagram account with over 5,700 followers to date!

Using only the most delicate of paintbrushes, rich paint colours made only from natural pigments so they don’t’ ever fade, special thick paper that is eventually burnished and mathematical instruments, she toils in a passionate quest to reclaim, revive and share in the beauty and intelligence behind a sacred Islamic Art based on the careful study of mathematics and Geometry.

Awartani: “Islamic art is firstly not made for the sake of making art. It is a sacred spiritual practice that is used as a way to worship God and for God. It teaches one sabr (patience) and respect and as an Islamic artist, my work is a form of prayer and dhikr (remembrance). I need to be 100% focused and in a good mood to be able to do it, otherwise it doesn’t’ work.”

When we met in London recently, I first noticed her modest feminine grace and how quiet but very determined this young woman is. She also has the inner light of knowing that her passion and purpose is to advance this rich but rather neglected and abandoned art form. I asked about her artistic journey and how she came to Islamic Art.

Awartani: “From the age of 14 I knew. During my Art GSCEs at the British International School in Jeddah, I was subconsciously drawn to a tapestry project with a patchwork of flowers, because of the patterns and colours. Later I realised that I have this special thing for geometry. My teacher at the time recognised a talent and advised my parents that I must go to Central St Martins.”

Central St Martins, London: Orientalism Project

Awartani did go to Central St Martins and completed a Foundation course and Bachelors degree. However, she said: “I felt struggling a bit and they don’t give you a lot of direction. Although it was amazing to be with very talented creative people, I didn’t’ really learn the technical skills. I was taught to think conceptually and to critique a contemporary art piece, but not so much on how to paint or draw.

“I also felt they would push me towards things that I really didn’t want to talk about as an Arab, like suppression or exile. I wasn’t fond of talking about our Arab culture in a negative way because then you just reinforce those stereotypes. I am not in exile and I don’t at all feel suppressed as an Arab woman.”

Dana’s final year project at Central St Martins was a strong indication of the future direction in Islamic Art and also in her bold challenge against any Western or other misconceptions that as Arabs or Muslims that we don’t have a unique and very rich artistic heritage to draw upon and rival all the others.

She said: “A lot of people, when they create art, they abide by Western rules. Even the popular artists, even when they take Oriental themes, they use Western forms. Why should they have to follow that? They should be more original and unique. The Arab world should make art as much as the Western world.”

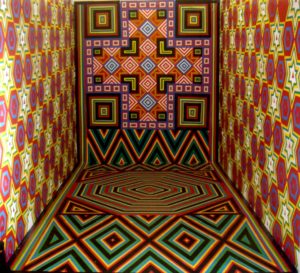

Inspired by Edward Said’s writings on Orientalism and working with the Saudi charity of ‘Mansoojat’ that preserves the dying art-craft of making traditional Saudi costumes, she created a provocative installation piece representing the Arab feminine space and covered it from the inside with colourful square and rectangular patterns as those stitched onto the textiles.

The room however was also sealed off by hundreds of black strings so that from a distance, it just looks like a black wall. It is only when one enters that they discovers the loveliness inside. She said: “I wished to create a place where people are not allowed to enter. It is kind of like if you don’t understand what our culture is about, then do not enter this space! It is also a nomadic temporary piece, showing our Arab background of not ever staying in one place.”

The Prince’s School of Traditional Arts

In 2009, Awartani enrolled on a two-year Masters course at The Prince’s School in Shoreditch, London where they specialise in the Traditional Arts. It is here she found a niche and felt more content, as she learnt of Islamic Art techniques and how to apply them to painting, woodwork, ceramics, miniature painting, mosaics, parquetry and stain glass, specialising in Geometry in her second year.

Under the guidance of Paul Merchant and Simon Trethewey, she more than found her niche but fell in love with the philosophy behind it and the foundation in how the infinite shapes, proportions, structures and numbers – found in both theory and in Nature – can inform her work. It is also with the firm belief that the physical is but a reflection of the spiritual and that nothing on this Earth has been created in a random vein.

It was not just the Arabs who pondered on the connection between Geometry and the divine, but also the Ancient Greeks. Aristotle, for example, drew a diagram of how the four classical elements of Air, Water, Earth and Fire create balance in the world; and, that above this, was the ‘Aether’ describing the heavenly bodies of the Moon, Planets, the Sun and Stars of a circular shape and motion. Different numbers can also be used as some kind of secret code or a language.

She explained: “Every number has a meaning but none of it is set in stone either and my favourite has to be the number Eight which is so beautiful mathematically, in numerology and geometry. The mystic Ibn ‘Arabi said that the eight-point star is a representation of the eight angels that bear the throne of God on the day of judgement and seen as a re-birth on a higher level.

“The Sufis also believe in the eight qualities of Prophet-hood that one must aspire to and it seems to be the same in Judaism, Buddhism and Christianity; where one must follow an eight-fold pattern of enlightenment or when baptism is done in an Octagon. The Rock of the Dome also was built on an 8-figure base.”

Currently inspiring her work are the ‘Platonic Solids’ based on the most ancient form of three-dimensional geometry. Named after Plato who studied them, they are the five perfect shapes that fit harmoniously within a circle and that all classical elements are made from them.

She said: “I love studying these and want to incorporate them in my work, because they are an expression of the creation on Earth and everything to be found in nature. They reflect how the world is proportionately and mathematically in harmony. Already, I have done five paintings for the Dubai Art Fair on the Platonic Solids and I am hoping to do much more, including sculpture.”

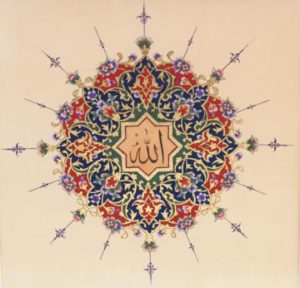

The Art of Illumination

Another aspect to Awartani’s work is the meticulous art of Illumination that originally developed to adorn Arabic calligraphy and Koranic inscriptions. Although very time-consuming with strict rules that cannot be manipulated, it gives her pieces that something extra by bringing in the illusion of more light, movement and colour.

Currently, she is working towards an ‘Ijaza’ certificate – the highest form of recognition and authorisation to eventually transmit the skill – in this highly disciplined subject; where one must first put on the gold, then the background colours and only after this, can you do the outline and finally the rendering. Visiting Turkey from time to time, she is set to complete the challenge.

Awartani: “It is only once I become an expert in traditional pattern and receive my Ijaza in Illumination that I will feel qualified to experiment; but I don’t think one should be changing the forms, because then it is not really Islamic Art, it is just inspired by Islamic Art. Maybe one can simplify it or take a certain motif and use that, but I don’t’ believe in changing the design completely.”

Although there are some keen collectors and centres dotted around the world that attempt to preserve the old mosques and palaces and some of the traditional Islamic Arts, like in Turkey, Spain, Iran and Morocco – this is still not enough as during the heyday of Islamic culture and the centuries worth of output.

She said: “We need to be very careful or this beautiful art craft is going to disappear. There are not many traditional craftsmen left; and even so, everything is mass produced, manufactured and industrial. In Morocco, for example, I know they don’t use natural pigments for their glazes but synthetic, which is horrible in comparison to the natural stuff. That is just an example of how it is deteriorating.”

Islamic Architecture And Building A Mosque

Awartani’s is also fascinated by the design and aesthetics of Islamic Architecture that is reflected in the iconic buildings to be found in Turkey, Iran, India, Spain and the Arab world. She has travelled extensively and been to the Alhambra in Andalusia, the Blue Mosque in Istanbul and the buildings in Isfahan, Yazd and Qom, as well as the Taj Mahal. Her next stop is Morocco.

She said: “I love the Persian architecture with its blues and turquoise colours, it is extremely feminine, whereas the Turkish is more masculine. The Alhambra for me is the most beautiful as well as the Taj Mahal. Although this latter is not a mosque, there are Koranic verses inside and the vision of angels to protect the lady buried there. Based on the eight-fold, its gardens represent paradise.”

One of her dreams is to design a mosque mixing the different Islamic traditions and to ensure there is no distinction between Sunni and Shia or other inner divisions. She said: “I hate how there is discrimination depending on which part of the Arab world you come from. We are disunited and need to unify. So I want to build a place where someone can enter and recognises that it is a mosque for everyone. It will happen but am not ready yet.”

It is time for us to part and she is returning to Jeddah to prepare for her next group show at the Athr Gallery and for the grand solo next year for which she has a few planned surprises that she wouldn’t divulge. So, I asked if she takes any breaks from the studio and what it is like to live in the conservative Saudi.

She said: “I just go up to the rooftop garden with my pet dog and muse Lady who is always with me or I take her out for a walk. Yes, the local traditions dictate that I wear the Abaya and veil to go out and be driven by a male chauffeur, but in Jeddah, I feel empowered as a woman and proud to be an Arab. I will continue to make art and Inshallah I will die with a paint brush in my hand!”

Awartani’s work has so far been exhibited in London (UK), Jeddah (Saudi), Abu Dhabi and Dubai (UAE), Venice (Italy) and Doha (Qatar). She also works with the Prince’s School’s International Outreach Programme where they train and teach the Traditiaonl Arts to schools and communities. Four of her pieces are also at the ‘Farjam Collection’ in Dubai.

Awartanis’ pieces can range from £500 to £8,000 – depending on the effort, time and cost of materials used – and be viewed via her personal website or Instagram or through the Athr Gallery. Rarely but possible, she can also take commissions.

For more on Dana Awartani: http://www.danaawartani.com/

For more on The Prince’s School of Traditional Artss: https://www.psta.org.uk/

For more on The Athr Gallery, Jeddah: https://www.athrart.com/gallery