Prefaced by his wife Isabelle Massoudy, ‘Calligraphies of the Desert’ is the latest collection of the master Iraqi calligrapher’s work as he turns his focus to the desert, published by Saqi Books. Here we find his signature art form as he ponders: the wonders of the sand dunes and their shifting nature, the reflective elements of the moon light shining down, the vision of the night stars, the feeling of space and the sound of silence, the movement of a camel, the Bedouin’s knowledge of his terrain, or the colour green as it portrays a welcome oasis for the thirsty traveller.

Leafing through this beautifully illustrated book, one is seduced into a thoughtful meditation – brief or long depends on the time you are prepared to give it – signalled by the artist’s calligraphic interpretation of the desert as a real place and as an imaginary one too. Inspired by the Massoudy couple’s world travels to different desert lands over a number of decades and their collating of texts, poetry and literature about the phenomenon of desert, you get the sense of figurative movement with the words that he paints, as each individual letter comes to hold much power and meaning.

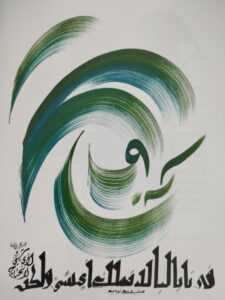

With a user friendly layout, the pages on the right side are used to display the artist’s larger works in colour, in which Massoudy’s expert touch utilises the motifs and shapes reminiscent of the desert, with his recognisable majestic strokes in warm yellows, reds, orange, dusky pink and some browns too. These pieces take on poems, proverbs and short mystical compositions written in the Arabic language, be they originally from the Middle East or having been translated. From Al-Mutanabbi and Rumi, to Kahlil Gibran, and writers from the West, including Goethe, Baudelaire, and Antoine de Saint Exupéry.

Whilst set on the opposite pages are smaller illustrations done in black and white that tackle one word concepts or singular ideas, such as the artists’ take on: liberty, beauty, splendour, water, light, the void, the camel, the well, water, light, the wind, among others. Again, each word becomes a cause for contemplation and feast for the eyes, the mind, the heart and soul.

Still yet the book includes Isabelle’s contribution of the longer texts taken from European travellers who have visited the Arab deserts that she had taken years to put together in personal notebooks. In the preface she mentions how, by the time they had visited the dunes of Mauritania, Algeria and Morocco, that: “I carried my little notebooks with me. The desire seized me to reread them in the solitude of the desert, in the very place where they had been conceived, as if to pay homage to those who had crossed it and suffered there, where some had died, yet where none had remained unmoved by it.”

A prolific artist who has been based in Paris, France for many years, Massoudy is most highly regarded, respected and renowned in the art world by significant art curators, critics, collectors and among other calligraphers throughout Europe and the MENA region. His works have been exhibited internationally and belong to many permanent collections at art houses, museums and institutions, including the British Museum.

Born in 1944 in Najaf, Iraq – a holy city well connected to the origins and development of Islamic calligraphy that is manifest in its architectural and religious fabric – he showed an early talent for the Arabic calligraphy and was pushed by an uncle and a school teacher to learn more, encouraging him to participate in local exhibitions. So that in 1961 he moved to Baghdad where he apprenticed under several calligraphers to study the classic techniques and styles for eight years.

But Massoudy had also wanted to explore fine art too and in 1969 moved to Paris where he studied at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts. It seems however that after five years there, he felt disheartened and didn’t know which direction to take. After some soul searching, he decided to somehow go back to his first love of Arabic calligraphy and sought out the renowned living masters then, namely Hamid al-Amadi in Istanbul and others in Cairo.

From an extract published in ‘Signs of Our Times: From Calligraphy to Calligraffiti’ by Rose Issa, Juliet Cestar and Venetia Porter, Massoudy once provided this personal statement, relaying: “By the 1980s, I abandoned oil and canvas in favour of ink and paper. I decided to work on abstract compositions based on the shapes of Arabic letters. Words have the capacity to impose shapes I hadn’t considered, through their meaning. This is how Arabic poetry became more appropriate in the course of my artistic practice. I approach the work of poets with the hope that their metaphors will enrich my visual artwork’.

And the rest, as they say, is history, as Massoudy went on to develop his personal style using the means of the classical Arabic calligraphy to visually paint the spiritual verse that inspires him; be it of a Sufi source, philosophic texts, old proverbs, or anything of a transcendental and almost four-dimensional nature. His pieces are a reverence for the word and respect for the sanctity of the alphabet.

He is considered today by some as the greatest living calligrapher, with a huge popularity and following. Much loved, admired and appreciated from the critics to the experts, the collectors and the younger Arab generations who have been influenced by his genius.

Rosa Issa, a prominent Middle Eastern arts curator who has worked with him, said to Nahla Ink: “For almost 50 years, Hassan Massoudy has been painting the wise sayings of poets from the East and West in his beautiful calligraphical brushes, emphasising on the poetry that is common to all, and should apply to all humanity.

“Words hung in our living rooms, to remind us of the beauty of our culture, aesthetically and philosophically. He also grabbed very early in his career the importance of publishing and making his work and its beauty available to all, and hence inspire young artists. Today despite his Parkinson fight, he continues to embellish the art of calligraphy with word sayings and wisdom that he continues to share.”

Moreover, Hassan has helped usher in the movement taking the ancient Arabic calligraphy into the contemporary and modern art world, raising and elevating it to entry into exhibitions in international art galleries, museums and onto the streets of Europe and the MENA region, especially with the new strand of the art form called calligraffiti.

So holding, touching and reading this new collection of Massoudy’s work – the third published by Saqi – becomes an invitation to take that minute to sit still and consider secrets of the world, nature and existence. It is to open oneself to receive the artist’s gift of wanting to spread a message of peace, joy and harmony with his intense devotional labour. From this collection looking at the desert, to his other works that have addressed love and verdant gardens; it is not to be skimmed over but savoured one Massoudy creation at a time!

And ending with my favourite piece: The Oasis

Note: The original colour works are on paper of two sizes 75x55cm or 65×50 cm. They are based on pigments and binders and the artist has used different tools: a flat brush or a piece of cardboard or a calamus (cut reed). The black works are on light paper and in smaller sizes. The majority of these calligraphies are available for sale.

Images used in this article are with kind permission from the artist and Saqi Books.

To buy the book: https://saqibooks.com/books/saqi/calligraphies-of-the-desert/

To learn more about the artist: https://massoudy.pagesperso-orange.fr/english.htm

Note: This Nahla Ink article was first published circa October 2020