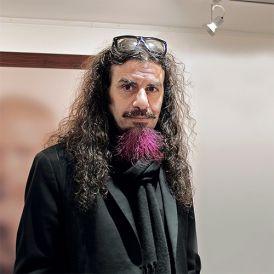

Halim Al-Karim: On Work, Women, War, Love and Politics

This interview was taken at the launch of the ‘Witness from Baghdad’ art exhibition held at the Artspace London Gallery in Knightsbridge, London on 16 January 2013. A review of the exhibition and the artworks has also been posted on Nahla Ink.

Nahla: Today’s exhibition comes at the tenth year anniversary of the Iraq War. You left in 1991, would you ever consider going back?

Al-Karim: No, not yet. But Iraq never left me. Always, it is inside of me. And I am not sure if I go back. I cannot imagine to arrive in Baghdad airport and then take a taxi and to ask the driver to take me to a hotel, because I don’t have an address there anymore. And I am not ready to go to face the lost ones.

Nahla: How do you feel about being in London?

Al-Karim: I don’t have any special feeling. I feel it’s like any other city but maybe just for the weather. Even the weather is the same.

Nahla: Looking at the range of work, what is your ultimate goal as an artist?

Al-Karim: I try to make my art for myself first, to control my beast and my monsters that exist inside me; and, through this, I try to let people control their own monster that exists inside of them too. I want to let people control their violence and show their best and to deal with each other in the human way away from violence.

Nahla: Tell me about your technique?

Al-Karim: I don’t think that technique is important for the audience to know about. But I will explain. I use different techniques, but always with a medium or large format manual camera, and I never use digital. I shoot the model sometimes with out-of- focus, I develop the negative and then I paint on the negative itself. Sometimes I also dip them in wax, let them dry and then scan.

For example, in the Schizophrenia series, I colored the negative and with the Lost Memory, I put a kind of white fabric in front of the model before I shoot with out- of-focus. Then you can see the results, the kind of shadow of the portrait.

I also use Lambda print, mounted onto aluminum so there is no air and little colour degradation. That way it is also easy to clean.

Nahla: What about the psychological element of your work?

Al-Karim: I don’t see any difference between me and society or between different societies. They all live in a schizophrenia. They follow their leaders, their governments and they elect them. At the same time, they know that these politicians have their own hidden agendas and their own deceiving policies, but they keep electing them. In this, my subjects are of universal themes.

Nahla: Tell me about the Seclusion series?

Al-Karim: This is an early work. It is called Lost Seclusion of the Soul, to represent the fear of my colleagues when they graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Baghdad.

Usually, they would take vacation from the army and every month, they give them seven days to go back to school. I saw the kind of fear and horror covering them. They used to be in the frontline for the war between Iraq and Iran and they told me how the sounds of bombs and bullets have affected them.

It affects them in the way they feel that they are isolated and I try to express this idea of how violence isolates people from each other.

Nahla: I heard a rumour that you have decided to stop making art. Is this true?

Al-Karim: If I ever stop dealing with women, then I will stop dealing with art. As long as I have women in my life, I will continue to make art.

Nahla: Some of your work has a very strong sexual element, can you explain?

Al-Karim: I am not sure on the idea of sexual freedom. I just present sexual pieces to express the idea of mercy, that people through sex look for mercy and how society considers women when they call them prostitutes. In fact, for me, they are not prostitutes, they are just creatures giving mercy to their clients.

Nahla: What about women? Do you think Arabic or Iraqi women are different from Western women?

Al-Karim: In general, there is no difference between women. It is just the propaganda that classifies women up until now. Even women in the West are not equal in their rights. For example, after they graduate from school or university and ask for a job, even when they get it, they are given a lesser salary than the man. This still exists in Europe.

Everywhere there is an injustice against women. It is not just Arab women. In fact, Arab women are educated and free but the war propaganda against the Middle East is focusing on this issue that women don’t have their rights. Actually, Arab women have more rights in the Middle East then women in the West.

Nahla: I love the Untitled 10, from the King’s Hareem Series. Can you tell me more about it?

Al-Karim: There are two ideas relating to this piece. The first is that I believe I am a creature or a man with nine hearts and all my life I am trying to find the goddess that can control these nine hearts and to make them tremble and shake at once. Because I believe the second I meet that woman, I will fly to my own paradise.

The second theme is about the situation all over the world affecting society and how people talk to their leaders and governments. It is to say we are full of anger at you and you have to stop your hidden agendas and deceit politics but through beauty. We are resisting this deception and policies through beauty.

Nahla: Tell me also about the Eternal Love images, which are being shown here for the first time.

Al-Karim: I will tell you about the theme behind them. I believe that eternal love exists in our lives. That is why in this series I try to visualize my lost memories through these pieces. Because when you live in hardship, usually your memory becomes full of holes and if you are aware about what is happening around you, then you start to close the holes of your memory and to collect the nice things that happen to you in life.

Note: This article was first published circa January 2013