An ugly shadow side of Libya’s history is that it was a slave market route for centuries under Ottoman rule, way before the Italian occupation and prior to Libya’s declared independence in 1951. Growing up in Libya, children might still hear stories from elders about the black maids who used to work in their household or about distant cousins in Africa who carry their same recognisable surnames.

There would be no elaboration on the reality of the trade that used to buy, sell and barter human beings and rarely admission of how the ancestors may have been involved in the mistreatment of those held captive. Few Libyans have the courage to revisit that period with its many ghosts or to bring up the racism issues that still persist in the culture.

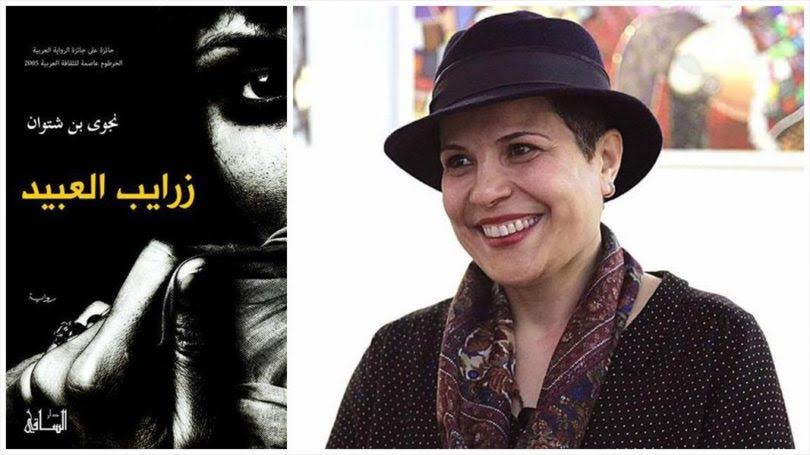

Not up until now that the talented author Najwa Benshatwan has taken the task to heart by writing a novel so powerful, beautiful and so sensitively fashioned in the narrative voice of the slaves. She has creatively wrapped it up into a love story that touches upon the era and the taboo subjects that have never been exposed before.

Shortlisted for this year’s International Prize for Arabic Fiction, ‘The Slave Pens’ has yet to be translated into English. Already, Benshatwan is being courted to turn it into different languages and to adapt it into a TV series or a film. This new positive intrigue by the literary world has been unexpected – as she has already successfully published two other novels and collections of short stories – but very much welcome.

For the Shubbak Festival 2017, I spoke with Benshatwan via Skype and we conversed in the Libyan dialect. She opened up not just about the book that will undoubtedly transform her artistic destiny; but, also, on the challenges she faced as a budding intellectual during the oppressive Gaddafi regime, how she managed to overcome obstacles put in her way and how she is now content to be in Rome, Italy where she can pursue her work without complications.

Benshatwan: “For a long time, I felt buried in Libya. Born in 1969, I was of the generations that were denied the right to learn European languages at school and it is still a source of anger for me that I don’t’ speak except very basic English. When I was young, my talent as a writer would be denied as my homework at the age of 11 became a source of suspicion amongst teachers, who could not believe that it was my work and not that of an adult.

“Later on when I went on to university in Benghazi, it was my beautiful handwriting in Arabic that was a problem. To trick my examiners not to recognise my paper, I forced myself to write with my left hand so they wouldn’t know it was me. I did also learn braille and sign language for a brief period when I specialised in working with deaf and blind children.

“In terms of my literary ambitions, under Gaddafi there was no intellectual freedom and I was always worried about not just the state control but family and societal controls too. It is only now in ‘The Slave Pens’ that I am much older and more confident that I can safely explore things like love and sex for example.

“So I turned to short story fiction and utilised symbolism when dealing with Libya as the essence and background of my tales. But I was careful to enter only competitions judged abroad and they were one way to gain recognition. But my work came to the scrutiny of the Libyan authorities who tried to lure me to write about the regime and its ideology which I refused to do.

“The situation worsened when I got arrested and charged for writing against the state with the publication my short story ‘His Excellency, the Eminence of the Void’. Afraid and terrified to spend a night in prison with criminals, I travelled all the way to Tripoli where I spent four hours under interrogation knowing that the maximum sentence could be execution.

“Although I was not convicted, they wouldn’t leave me in peace, making my life hell and sending spies at the university where I was teaching and forcing me to attend political events. It was like cat and mouse that I stopped publishing my work and planned to save up enough money to be able to make an escape.

“But things changed with the February Revolution. I had naively believed in the rebel fighters and the struggle so much that I gave them my savings. Then sadly realising that there would be no security in Libya, my next chance to leave came when I got accepted to study in Italy where I have been for the past four years.

“My time in Italy has not been easy. I have been lonely and had to face dire economic circumstances and the psychological turmoil that entails. I had to take all sorts of jobs to survive and it took time to learn Italian before I could complete my doctoral degree at La Piensa University in Rome.

“I wanted to dedicate my thesis to the slavery and human trafficking under the Ottoman period and the Islamic Empire because I was haunted by a black and white picture that I had seen in an Englishman’s traveller book… although I cannot remember the name of the book or the Italian photographer who must have captured the image around early 1900s.

“It was of black women slaves with a boy and a child. When I asked about the scene, I was told that the quarters where they used to live were commonly referred to in the local dialect as ‘pens’ in the way of an animal’s pen. I had the photo scanned and put as my screensaver since 2006.

“For years I couldn’t steal myself away from the characters and my imagination became immersed in contemplating their lives… that is what urged me to write and finish the novel. My hope for it is to be a wake up call for Libyans to learn from past mistakes and acknowledge how black slavery – both past and present – has impacted on our society, from the economic to the social, political, cultural, psychological and mental aspects.

“Overall I am happy to have explored this subject and I am proud to be the first Libyan woman to be shortlisted for the IPAF. I can now finally be able to dedicate more and more of my time to just being a writer.”

Benshatwan is scheduled to participate in the ‘Under The Radar’ talk that is part of the Shubbak Literature programme at the British Library. This interview article was written in collaboration with the Shubbak Festival 2017.

For more information about Shubbak Festival: http://www.shubbak.co.uk/

Note: This article was first published circa July 2017