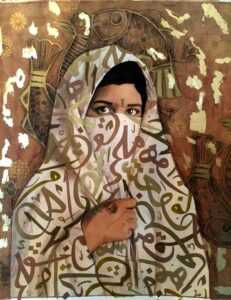

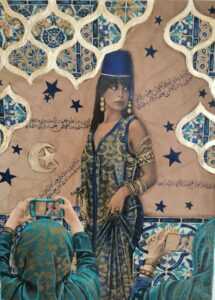

To resonate with this emotionally harsh season, Nahla Ink is featuring the works of the artist Hani Zurob, who has sacrificed years of his life for being Gazan, forced into exile from his Palestinian homeland for 16 years. Much of his art, not all of it, touches upon how the geopolitical can influence the personal; and, how that also impacts on universal themes of identity, place and memory, as well as the specific states of suspension, delay and waiting, alienation, movement and displacement, absence and resistance.

I personally got in touch with Zurob recently, when I came upon his Instagram feed. Scrolling for visual accounts interpreting the current hell scenes on our computers, Tvs and mobile screens, I was drawn to the intense energy emanating from his pieces that date back in recent time. When no rational mind can make sense out of the disproportionate Israeli punishment against the defenceless innocents today, I had to turn to artists for respite and momentary closure; they alone are alchemists, able to turn human ugliness and psycho-pathological madness into psychic gold, beauty and power.

“I was always trying not to believe that we were alone. But unfortunately: how alone we are in the sea of humanity’s darkness.” Hani Zurob

Of course Israel’s violence is nothing new to the Palestinians, marked in the textbooks by the Al Nakba of 1948, which saw the forced expulsion and dispossession of the Palestinians, as well as by later Nakbas. We all know, also, that the original ‘catastrophe’ can be traced back to the arrival of the Zionists in Ottoman-held Palestine in the late 19th Century, whose cause was expedited by the British with the Balfour Declaration in 1917.

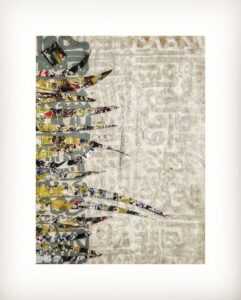

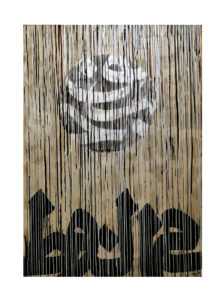

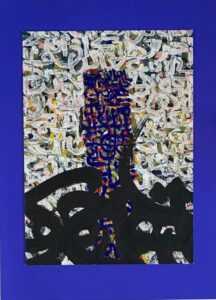

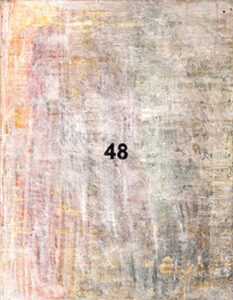

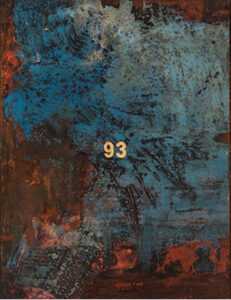

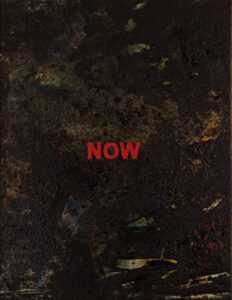

Now-93-67-48, 2016, tar and mixed media on canvas, 200 x 65cm, Institut du monde arabe collection

In an insightful interview article by Italian journalist Naima Morelli for Middle East Monitor (MEMO) published in January, 2022, Zurob pointed out: “For a Palestinian who is in exile it is difficult to quantify or qualify one’s losses; your struggles for your right to live become a constant. As for my gains, they lie in my art practice and art; my art is my heaven, it is the compass of my Self and Soul without which I am lost.

“When one is not deeply connected to one’s Soul, life will be gruelling… I reached that point through my constant inner quest into the Self and the journey to purify the Soul; this for me is my victory over any form of threat.”

Now-93-67-48, 2016, tar and mixed media on canvas, 200 x 65cm, Institut du monde arabe collection

Although the Palestinian tale is old without a foreseeable just end, it happens to affect each and every single one of us. Voluntarily or not, we are bearing witness to the tip of an historic genocide, of an Occupier state brutalizing women, children, journalists, academics, musicians, and artists who have done absolutely nothing wrong.

Ignorance is not really an optional alibi; and, especially, as we have awoken to the complicit inaction by powerful governments, who continue to protect Israel, and stubbornly refuse to do the right thing. Even as the millions peacefully protest ‘Not in Our name’, nothing has shifted; making us all swallow the bitter pill of double-standards and hypocrisy.

No matter, the dirty politics will continue and the unholy wars will be waged, until the end of the human story on the earth. What becomes relevant is what can be done in the meantime to empower the wounded soul and satisfy the ethical balance, guided by our desperate need to still believe in some form of karmic justice. Again, this is where artists have always walked ahead of us, I trust them to be my friends in these worrying times.

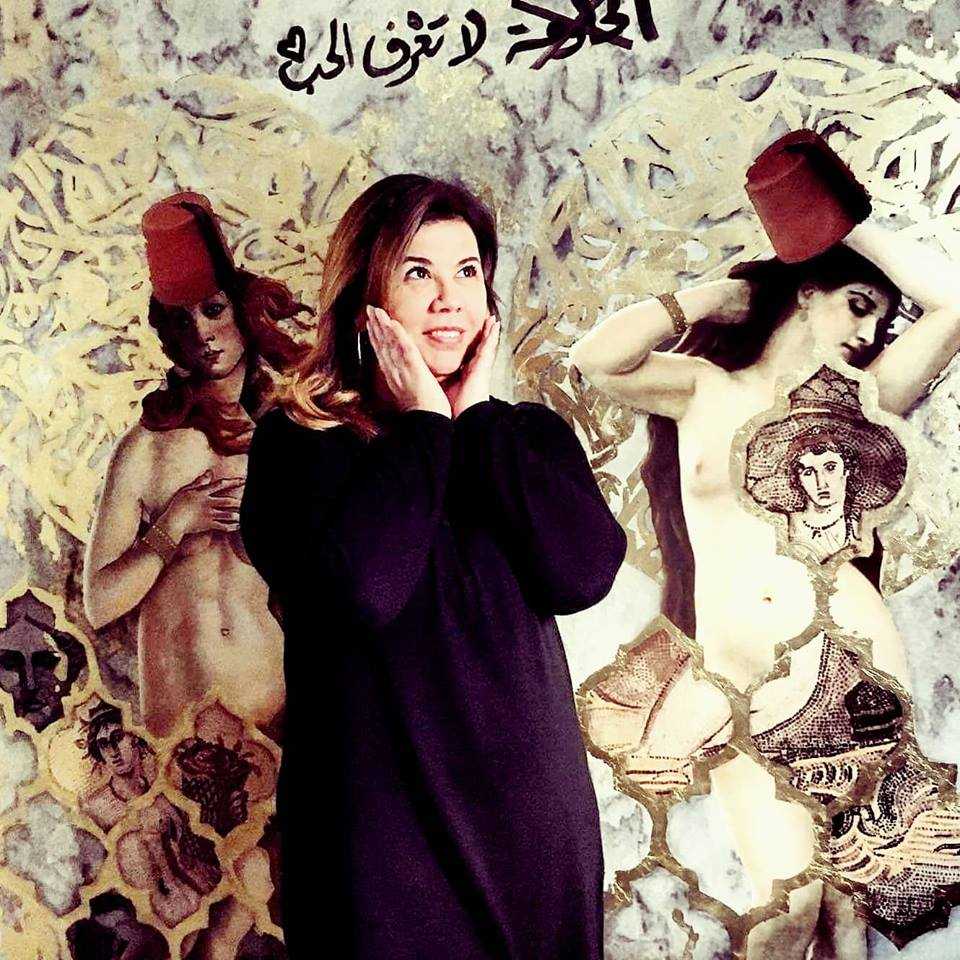

Artist Biography – Courtesy of the Artist

Hani Zurob [b. 1976 in Rafah camp, Gaza Strip, Palestine] is a contemporary visual artist who has been living and working in Paris, France since 2006. He obtained his Bachelor’s in Fine Arts from Al-Najah University, Nablus in 1999. In 2002, while living in Ramallah, he was selected as a finalists of the A. M. Qattan Foundation ‘Young Artist of the Year’ Award that was a turning point for his future career, topped by a residency grant at Cité Internationale des Arts, Paris in 2006.

Zurob’s pieces tend to conjure private experience and the stories that have shaped his life; and, in particular, how these connect to the unfolding events in Palestine, carrying both political and cultural dimensions. Searching and researching memories, the artist deconstructs the relationship between the past and present, on himself and others, to be able to transcend borders and geography.

In terms of material, Zurob selects media to the extent of its literal meaning or, at times, pointing to metaphorical associations to amplify his message. Most notably, he uses tar, which has allowed him to present a unique contextualized vision of Palestine, referencing the time of youth up until the present age.

Residing in Paris, he has forged a successful career with exhibitions held worldwide and having been the recipient of many Arab and international awards, including Renoir Stock Exchange Prize, France (2009). Today, he is considered one of the most brilliant and influential Palestinian artist of his generation.

His work can also be found in several prominent private and public art collections, including those of: The British Museum (London, UK), The Arab American National Museum (Michigan, USA), Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova, MSUM (Ljjubljan, Slovenia); Williamsburg Art & Historical Center (New York, USA); Institut du Monde Arabe (Paris, France), Barjeel Art Foundation (Sharjah, UAE), Dalloul Art Foundation (Beirut, Lebanon), Jordan National Gallery of Fine Arts (Amman, Jordan), among others.

In 2012 a monograph tracing the evolution of his work, titled ‘Between Exits: Paintings By Hani Zurob’ (Black Dog Publishing, London), was compiled by Kamal Boullata, including an introduction by the late art critic Jean Fisher.

“Hani’s practice provides an important voice in contemporary Palestinian culture, as well as a significant contribution to the creation of an Arab aesthetic. Ultimately though, while Zurob’s art gives powerful expression to the Palestinian collective experience, it can also be seen in the context of more universal themes of personal identity and embraces humanity beyond the Palestinian context.” Kamal Boullata

For more on the artist: https://www.hanizurob.com/

To follow his Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/hanizurob/

I highly recommend reading the full MEMO interview article by Naima Morelli: https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20220126-floating-in-tar-interview-with-palestinian-artist-hani-zurob/